[vimeo 6031524 w=500 h=281]

The Gershwin Piano Quartet plays Gershwin’s “I Got Rhythm.”

[vimeo 6031524 w=500 h=281]

The Gershwin Piano Quartet plays Gershwin’s “I Got Rhythm.”

August Weger, Engraved Portrait of Chopin, based on a painting by Ary Scheffer from 1846. Yale.

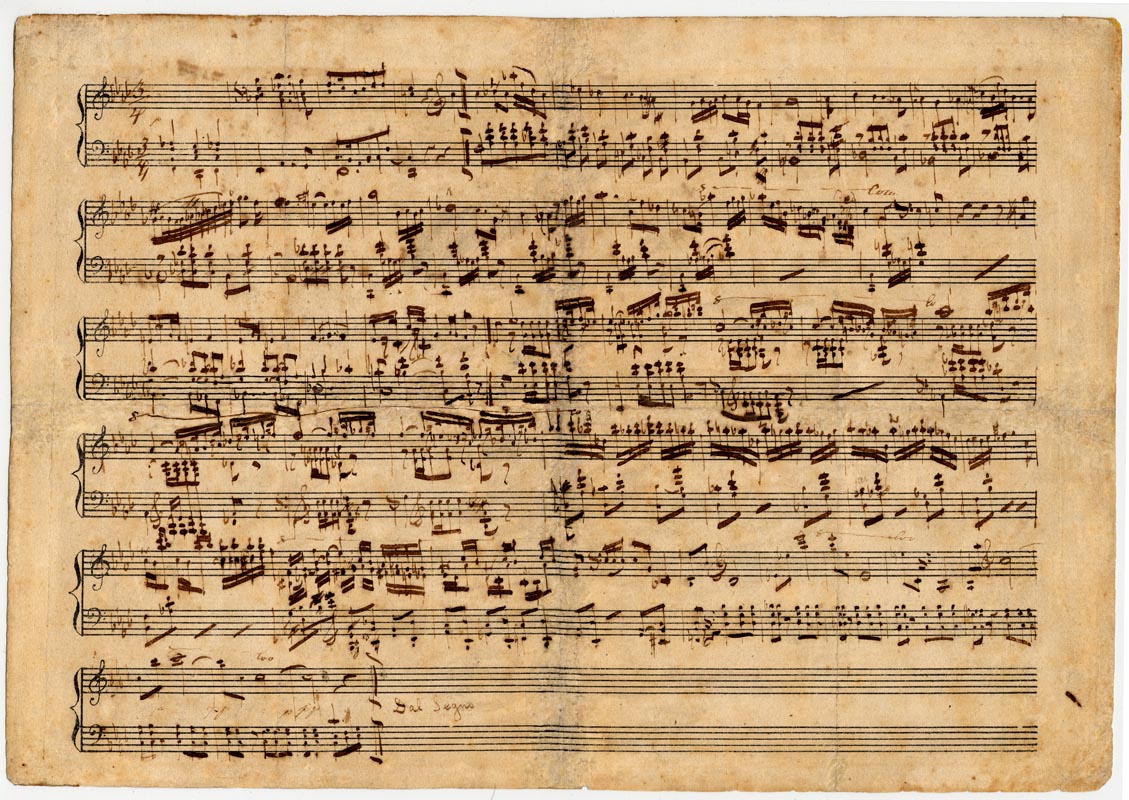

Chopin’s manuscript for the Polonaise in F minor, Op. 71, No. 3, ca. 1828-29. Yale.

Chopin owned one of these, a fortepiano by Conrad Graf. Metropolitan Museum.

[vimeo 20944705 w=500 h=409]

Sviatoslav Richter plays Chopin’s “Revolutionary Etude.” Richter was a force of nature!

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VJNsA67hVzg?feature=oembed&enablejsapi=1&origin=http://safe.txmblr.com&wmode=opaque&w=500&h=281]

Gautier Capuçon, Michel Dalberto: Fauré, Sicilienne

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fSmMbp22JKI?feature=oembed&enablejsapi=1&origin=http://safe.txmblr.com&wmode=opaque&w=500&h=281]

Renaud Capuçon, Michel Dalberto: Fauré, Berceuse Op. 16

by Matthew Raley [youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6cxkLZoEFEk&feature=related]

I was introduced to Chopin's music by a record of Pollini, so I'm grateful to the man. Here he is playing Chopin's Nocturne No. 8. What I like about this is not just Pollini's clarity and musicality, but also his insight. He teaches me that Chopin is about simplicity. The pianist who can command the virtuosic passages to serve the composer's simplicity this way is the one I want to hear.

by Matthew Raley [youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=av2XTNgA72w]

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Gmf4Z9HsnFQ&feature=related]

I have written elsewhere about the entertaining contrasts between Glenn Gould and Yehudi Menuhin. In the first video, the contrasts are amplified as the pair converses about Arnold Schoenberg's Fantasie, Op 47. In the second, we see another example of the duo's partnership.

In one sense, I don't know why I post these. People usually hate Schoenberg. Added to this is the fact that the discussion between Gould and Mehunin is at a high technical level.

But, dog-GON-it!, they're saying some important things about real musical problems, especially after Gould says, "All cards on the table, you really don't like the Schoenberg." And the playing is quite good, demonstrating that Menuhin retained even post-war a powerful tone and intonation when he was "on."

So, if you've never heard anything by Schoenberg, take this in.

By the way, my 3-year-old Malcolm sat silently on my lap through the entire 10-minute performance, transfixed. (No jokes there in back!)

by Matthew Raley No excerpts today, but a complete work in a film that is fascinating at many levels. Start with the performers, Glenn Gould and Yehudi Menuhin. It would be hard to find two more different characters.

Gould was eccentricity incarnate, seen here making a circular movement with his head that is, shall we say, unsettling, and seeming to talk to the keyboard. You can also, of course, hear him singing.

Menuhin was a study in elegance. Not only his left- and right-hand positions, but his posture and his tailoring are flawless. He has an economy of motion that is inspiring.

So, behold, the cherub and the gargoyle.

The piece itself adds another layer of interest. Bach's Violin Sonata, BWV 1017, is a powerful work, and the third movement (pt. 3) is a favorite of mine. But the question always is, "How will the performer interpret this music?" Today, there is a consensus that we should play it Bach's way -- light, dance-like, less vibrato. This is a consensus I basically agree with.

At the time this film was made, the romantic interpretive approach to Bach was beginning to sound inauthentic. The heavy articulation, the dark tone, and the sentiment expressed in slides and accents, all turned counterpoint into a soup.

That is why Gould had formulated a modern interpretive approach to Bach at the piano. It was unsentimental: dry, spiky, fast. Some would still criticize his approach as mechanical. Gould was a controversial figure, especially for his 1955 recording of the Goldberg Variations, a sharp departure from the romanticism of the time.

Which brings us to the really fascinating layer of this film.

Gould is playing with the man who popularized the romantic style of playing Bach on the violin. Menuhin is credited with bringing the unaccompanied sonatas the attention they deserve from audiences in the 1930s. He plays here with all his famous warmth of tone, all his sustained vibrato, and even with one or two slides. (It is also the case that his intonation is no longer secure, but that is another difficult story.)

See if you don't agree with me, you music lovers, that these two men achieved a common interpretation that works. I believe it has power even as the performers retain their musical personalities. Something of the contrast is part of that power. But their ensemble, their unity on such things as the length of 8th notes in the fourth movement (pt. 4), and their authority in playing the piece, all create an unusual synergy.

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Uz2TnU5dJSs&feature=related]

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cbzWLnBl4oM&feature=related]

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ccuawruSsqc&feature=related]

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MFMKCUuGh5o&feature=related]

by Matthew Raley [youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iTpAIEp6DUo]

Paul Hindemith wrote a piece of music for every instrument in the modern orchestra, which distinguishes but does not necessarily recommend him. I often find his music sterile. But not this fugue from the Piano Sonata No. 3.

This piece has it all: rhythmic interest, contrapuntal high-wire acts, atonal harmonies that sometimes imply tonal colors, and drama.

I say the piece is atonal, but that needs some qualification. The fugue subject is broadly and recognizably from the world of the scale, and the piece works its way toward a cadence that would have offended Theodor Adorno. But Hindemith makes no attempt to keep the harmonies produced by his counterpoint within even the outer frontiers of the common practice period.

Glenn Gould's playing is powerful, as always, and his mannerisms not as eccentric as they could be.

by Matthew Raley [youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eQpsL_kh6pE&feature=related]

Mitsuko Uchida has an endless variety of pyrotechnics to use for encores, short pieces played at the end of a concert as a kind of bonus for the audience. But here Uchida gives a quiet reading of the 2nd movement of Mozart's Piano Sonata in C, K. 545.

I didn't know the piece, but only clicked it to hear Uchida. This bit of late Mozart is rich, and her performance froze me in my seat until the last note.