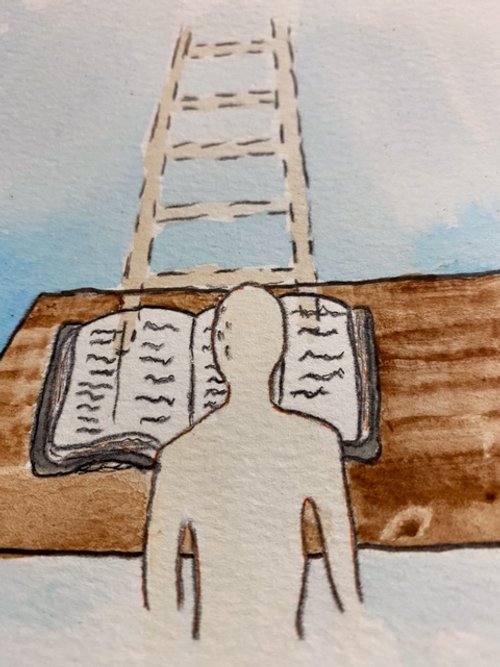

The Ladder to the Invisible God

Illustration by Paul Mathers

One of the most important theological events of our time is unfolding today, a rediscovery of the nature of God. The rediscovery is emerging out of a debate among evangelicals that will have consequences for generations to come. It is also a personal rediscovery, helping me decide in a fresh way what it means to be a Christian.

Evangelicals are debating whether God has being in himself alone. What kind of being is God? How does he exist? What do we mean when we talk about God’s attributes, like eternity or holiness? Is God dependent on other beings?

One side in this debate is called classical theism, and its foundational doctrine is that God is absolutely independent in his being. He has life entirely within himself. The technical term for God’s absolute independence is aseity. This tradition of classical theism stretches back to the church fathers—and many of us would say, to the Bible itself.

More specifically, the debate is whether God changes, suffers, is bound by time, or can grow or diminish as a result of his relationship with us. The range of positions is broad, from open theism (God changes over time) to what James Dolezal has called theistic mutualism (e.g., God sovereignly decides to change for his own reasons). Classical theism says that God does not change, suffer, or experience time as a limit. God does not grow or diminish. His being is absolutely independent.

Today, many evangelicals instinctively say, “Of course God changes in relation to us. God even needs us. That’s why he created us and saved us from sin.”

A changing God is very much what many evangelicals want.

How they respond to this debate will decide the future of Christianity in America. If evangelicals deny God’s absolute independence because they want a God who “needs” them, they will quicken their steady slide into incoherence and decadence.

I am joining this debate less as a scholar than as a pastor. Craig Carter and Matthew Barrett among many others are moving the scholarly discussion with forceful arguments about, for instance, the role of metaphysics in credal faith. I am happy to learn from their work and have little to add.

Instead, I am focused on the strength that classical theism gives to devotional and congregational life. There are three issues that I will be addressing in weekly posts.

First, the Bible calls all Christians to disciplined thinking. From the beginning of the church, Christians understood that their ideas about the nature of the world needed to be clear. But today many congregations have been taught that the Bible comes with a plug-and-play approach to modern life, as if we shouldn’t have to think about Scripture much. The Bible is truly all-sufficient for constructing our view of the world, but we still have to do the construction work. The Bible is our ladder to God’s invisible being. We need to climb it.

To assume that we automatically understand how the Bible’s truth applies now is inept and negligent.

Second, the Bible reveals a God whose being is the ground of our own. We have nothing without God—no space, no light, no sustaining air or food, no life at all. The best life for us is to rest in our creaturely dependence on the independent being of God. When we feed our spirits the junk food of sentimentality (“God needs me!”), we create an upside-down world.

He doesn’t need us. We need him.

Third, the Bible shows that emotional health comes from being a worshiper of God. We gain peace, joy, and hope when we adore God’s greatness. But we imprison ourselves in fear and anger when we live in a fantasy world, one where God is less than God and we are more than creatures. We rage against a world we cannot remake. And we rage against God himself, who stubbornly refuses to relate to us on our own terms.

I am not writing on these issues out of mere intellectual interest, but out of personal need. My family has been hit with many losses in the last several years, culminating recently with the death of a young woman dear to us. The accumulation of grief often leaves me feeling lost, questioning where I should put my foot next and wondering whether my path ever mattered.

I am writing on the doctrine of God not so much to convert you as to convert myself.

I am rediscovering that God is most deeply good when he is most truly God. My rediscovery is coming in the midst of temptations. Sometimes I want to make a little totem that comforts me and call it Jesus. Other times, I want to reject God entirely. Those temptations are forcing me to confront the emotional reality of losing the living God.

I am coming to the realization that I would rather lose every grand illusion than the least detail of God’s being.

Please subscribe and stay tuned!

Our illustrator for this new series is my colleague, brother, and friend Paul Mathers. He is an elder at Living Hope Fellowship in Chico, CA. Paul has generously agreed to react to these posts with his watercolor brush, and I am grateful to him.